What The Matrix, Inception, and the Food Industry Can Teach Social Media Sites about Truth

It’s a classic scene from one of the seminal science fiction movies of the late 20th Century. The hero and his party of ragtag soldiers are deep in enemy territory. He sees a black cat walk by a doorway and then, seconds later, another black cat. He makes an exclamation which is noticed by those around him. The hero claims to have experienced déjà vu, but intense questioning reveals that déjà vu is a sign that something has changed in the virtual prison known as “The Matrix”. This glitch is a reminder that the Matrix is a fake world separate from the real world.

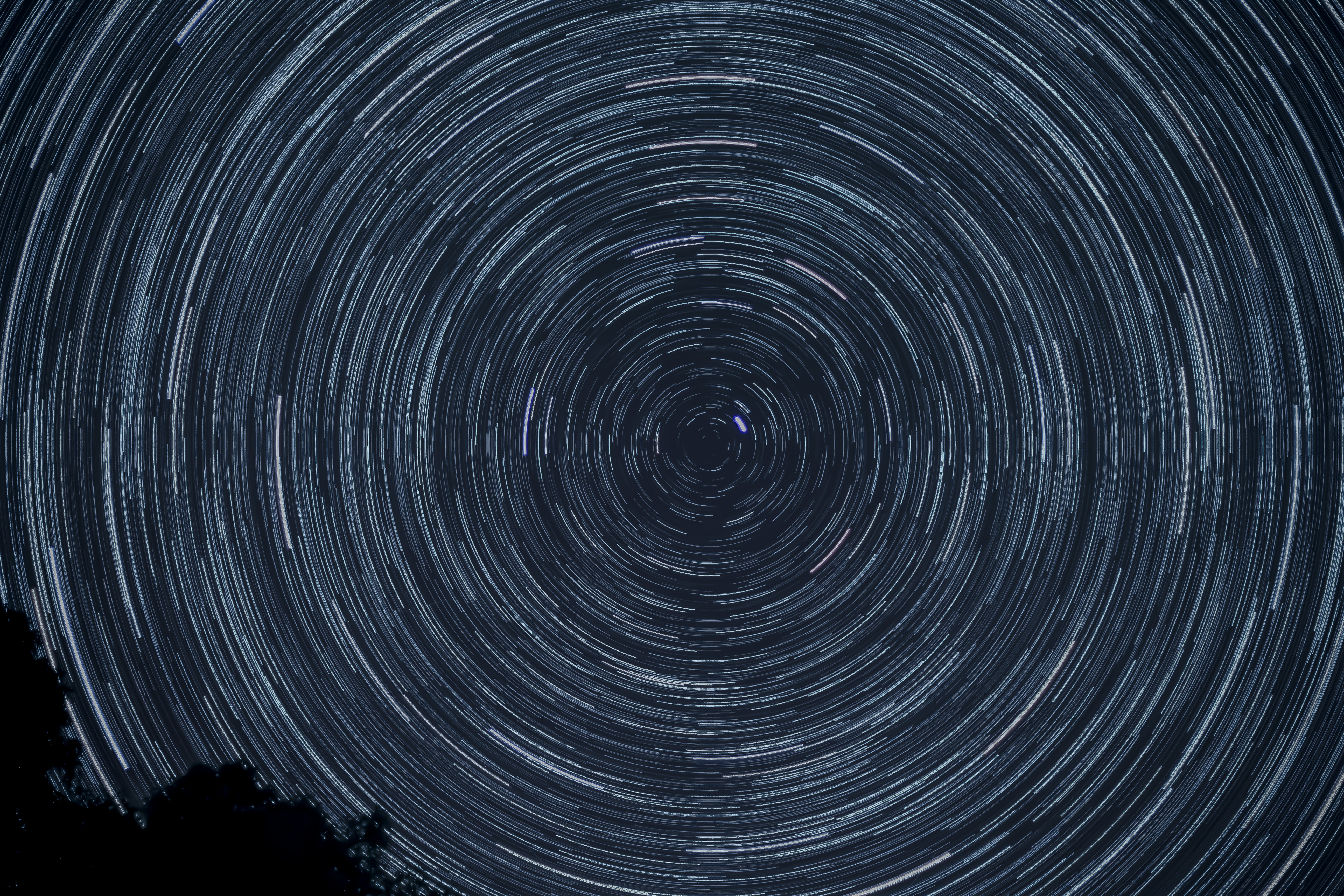

A similar “tell” exists in another science fiction movie called “Inception”. In this movie, multiple people can share a simulated world presented as a dream where it’s impossible to know if you’re awake or asleep. However, experienced navigators of the simulation learn to use an item known as a totem to determine if the world they are experiencing is real. The hero’s totem in the movie is a spinning top that rotates forever in the dream world.

Neither “The Matrix” nor “Inception” explain why the fake worlds at the center of each film included ways for the characters to know whether or not they were in the real world. Were they put there on purpose or were they truly providential technological defects? Regardless, our current world could use similar tools to distinguish between what is real and what is fake. This is especially true for the millions of people who use social media sites.

The Growing Danger of Social Media Influence

There is growing and almost incontrovertible evidence that a hostile foreign nation used propaganda to influence the 2016 presidential election in the United States. This was done using a combination of various tools including widespread propaganda shared on social media sites as well as alleged collusion with the candidate who won the election.

As we continue to live more of our lives on social media platforms while those sites become attack vectors used by foreign nations to influence citizens, social media companies have a growing responsibility to identify the truthfulness of the information presented to their users. Social media sites have to go beyond just optimizing the effective sharing of content. They have to explain the context of that content and provide an assessment of the health of the information.

Despite the evidence that social media sites were used to spread foreign propaganda, little can be done to convince the giant technology companies behind these sites to assist in any investigation. They can claim that the vast complexity of their computer systems make it difficult to easily explain how they were compromised. Or, given the multi-billion dollar valuations of most of these companies, they can hire armies of lawyers and lobbyists to defend them when pressed by government officials.

So, it’s possible that social media companies will continue to avoid accountability for the potential harm they can do to their users and to the nation. Ordinary Americans may be left on their own to distinguish real information from false propaganda.

Solving Disinformation in the Food Industry

However, this isn’t the first time that American citizens needed large and powerful companies to protect the interests of the everyday people who use their products. The current presence of nutrition labels on nearly every food product came about because of a similar struggle to reduce confusion in a complex industry controlled by powerful corporations.

Until the mid-20th Century, most people ate meals that were prepared at home or in restaurants using fresh and locally sourced ingredients. However, processed foods full of sugar, sodium and preservatives began to enter the American diet in the 1950s, and the link between poor eating habits and bad health began to be realized. Reports from the scientific community showed that diets high in calories, saturated fat, sugar, and sodium increased the risk for obesity, cancer, diabetes and other diseases.

American interest in the content of their food began to grow, and food manufacturers began adding labels touting the health benefits of their products. However, these claims were sometimes misleading and the information was more marketing material than objective factual information that could be used to make healthy choices. As artificial colors and sweeteners were added to the packaged goods in grocery stores, consumers struggled to tell the difference between real food and highly processed food.

A report by the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health issued in 1970 encouraged food manufacturers to include additional information about the nutritional value of their products. This included cautionary information like calories, fat, and carbohydrates as well as positive components like vitamins and minerals. However, this was done on a voluntary basis and the resulting product labels varied widely in content and accuracy.

Food manufacturers in the 1980s continued to game the labels by adding statements like “extremely low in saturated fat” as well as other ambiguous claims. They also began to market the health benefits of their products by using newly emerging research that linked the fiber content of their products with the reduction in risk for certain cancers.

Nutrition Facts Labels

Members of Congress and various federal agencies began to advocate for more accurate information from food manufacturers about their products. These efforts to standardize how manufacturers presented the nutritional value of their packaged goods culminated in the passage of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (NLEA). The FDA was empowered to make nutrition labels mandatory as well as regulate the contents of those labels. Other federal agents that regulated products outside the control of the FDA also supported the efforts the implement nutrition labels. This included the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) which regulates meat products as well as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) which regulates alcoholic beverages. Called Nutrition Facts panels, these labels are now so ubiquitous that most Americans don’t remember a time when they didn’t exist on food products.

The FDA found that visual presentations (e.g., bar charts and pie charts) of nutritional information were confusing to consumers. So, the FDA decided that a simple table of information should make up the Nutrition Facts label. This included the % Daily Value (or %DV) which showed the recommended amount of each nutrient that should be consumed in a day by a healthy adult. In addition to the the %DV, the serving size, servings per container, and number of calories would make up the information presented on the Nutrition Facts labels.

In the lead up to the passage of the NLEA, the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was Dr. Louis W. Sullivan. Secretary Sullivan stated, “The grocery store has become a Tower of Babel and consumers need to be linguists, scientists and mind readers to understand the many labels they see. Vital information is missing, and frankly some unfounded health claims are being made.”

The Tower of Babel of food labels was torn down, but social media sites now operate in the shadow of a similar edifice. Consumers of social media content need to be investigative journalists, scientists, and policy wonks to understand the many online articles they encounter. Burdening users with the responsibility of parsing the information they see on social media sites as unfair as expecting shoppers to expertly analyze the nutritional value of the food they buy in grocery stores. The Nutrition Facts labels that help consumers navigate the maze of the food aisle can be applied to social media content in the form of Veracity labels.

Social Media Veracity Labels

Just as food manufacturers tried to game food labels when they were voluntary and unregulated, we can expect the companies behind social media sites to do the same if given the opportunity to freely apply Veracity labels. After all, many of these companies feel little obligation to attest to the truthfulness of the information shared on their systems. They are essentially media companies designed to present content in a manner that draws users and serves advertisers. So, given them free reign to structure how they label the truthfulness of the information on their sites may result in more confusion and could even assist the spread of propaganda.

Similar to the food industry, an argument can be made that false information shared on social media sites should be a matter of public health and the proper functioning of our government. Thomas Jefferson said, “A well informed citizenry is the best defense against tyranny.” False information spread using the massive reach of social media sites can make citizens vulnerable to tyrants both foreign and domestic.

It is likely that a federal law like the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act will be required to make information labels on social media sites mandatory and consistent. The Federal Communication Commission (FCC) is the primary federal agency that regulates the internet, but other agencies will probably have to get involved. This includes the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and, given the possible threat from foreign countries, the Department of Defense.

The content of Veracity labels will have to help users of social media sites judge the truthfulness of the information they encounter either shared by other users or presented by targeted advertisements. A few reasonable measures include anonymous or dubious authorship, excessive quotes from sketchy sources, poor spelling and grammar, excessive use of exclamation marks and capital letters, use of outdated material, and links to poor sources. For advertisements, social media sites should be required to publish the currency used to purchase the ads on the information label since that may reveal possible foreign influence.

Just as the FDA found that using complex graphics on Nutrition Facts labels led to greater confusion by consumers, Veracity labels on social media sites should be simple tables. Each measure should be presented as a percentage, and the label should be consistent across social media sites just like Nutrition Facts labels are consistent across various food products.

Users of social media sites often complain when any design or functional changes are made, and they may complain about the introduction of Veracity labels. However, these Veracity labels can be designed to be subtle and unobtrusive. For example, the Veracity label may only be displayed when the user’s mouse hovers over the article or advertisement. Or, if using a touch screen, the Veracity label can be presented as a pop up when an article or advertisement is touched. Just as consumers don’t think of Nutrition Facts labels on food as odd or a waste of space, they will eventually normalize Veracity labels on social media sites and start to expect their presence on all content.

Veracity labels would present benefits for both social media companies as well as the users who consume the content of those platforms. The companies would have an incentive to improve the quality of the information on their platforms by building into their products a way to measure the accuracy of articles and advertisements. Consumers would have an easy to understand way to determine the truthfulness of the content they consume.

The déjà vu effect in “The Matrix” and the totems in “Inception” were plot devices to give the protagonists a fighting chance as they navigated dangerous virtual worlds. Mandatory and federally regulated Veracity labels would help users in the real world navigate the difference between what is real and what is fake on social media sites.